Introduction

Two or more genes are homologous genes when they share a common ancestral DNA sequence. Homologous genes in different species are considered orthologs of each other. For example, the mouse gene that codes for the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase is an orthologs of the rat gene encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase , and both are orthologs of human pyruvate dehydrogenase.

Since the DNA sequence of orthologs are not identical, orthologs can have slightly different properties. For example, the mouse version of an enzyme could have 10-fold greater catalytic activity than its rat counterpart. This variation in an enzyme’s properties could be beneficial for the organism if its environment changes and presents a new selection pressure.

Sometimes, the benefit may be obvious. For instance, if the world suddenly only has lactose as a viable food source, and mice have a faster lactose metabolizing enzyme than rats, they would clearly have an advantage over rats. This is an example of selection acting on the native activity of an enzyme.

It could be, however, that the variation in the rat lactose metabolizing enzyme by chance allows it to perform additional function(s), metabolizing charcoal, say. This alternate function could give the rat an advantage under a different selection pressure - such as if the world suddenly only has charcoal as a viable food source, say. This variation in a non-native activity of an enzyme is usually hidden until a selection pressure comes up, and is called ‘cryptic genetic variation’.

Cryptic genetic variation can play an important role in evolution, because it provides an organism with a “hidden” ability to adapt to a new environment. But how do we know which variant does best? Are some variants ‘pre-adapted’ to the non-native activity, or can any variant develop high non-native activity? Do different variants adapt using the same solution, i.e. the same set of mutations, or are they constrained by their starting point? And lastly, how do these mutations increase fitness, mechanistically?

The best way to answer such evolutionary questions would be to allow evolution to take place under controlled selection pressures, i.e. experimental evolution. We chose to perform directed evolution, a process that mimics natural selection to reachget a pre-defined and testable end-point of an experimenter’s liking. In this caseHere, the desired end-point is set at the enzyme (organism?) developing would be high non-native activity. Once the end-point is reached, we can trace back how different orthologs evolved to obtain this non-native function, and ask whether they used similar or different strategies, and what the molecular details of the evolution strategies are.

To start such experiment, one needs a molecule that has known variation between orthologs, as well as a non-native activity that can easily be measured and selected for. Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) are a genetically diverse enzyme family that confer resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in bacteria by catalysing the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring. Our previous work demonstrated that most MBLs also exhibit phosphonate monoester hydrolase (PMH) activity .

Having identified several orthologs with a known “non-native” activity, we used the MBL gene family as a model to study cryptic genetic variation in evolution.

Results

Comparative directed evolution of four orthologous MBLs

We chose four variants of MBLs as starting points - NDM1 (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1), VIM2 and VIM7 (Verona imipenemase 2 and 7) and EBL1 (Erythrobacter β-lactamase 1). These variants are orthologs, since they come from different sources. VIM2 and NDM1 were chosen because a lot of their biochemical and structural data is available. The others (VIM7 and EBL1) were chosen because of their high degree of homology with the first two: VIM7 and VIM2 share 80% amino acid sequence identity, while EBL1 and NDM1 share 55%. All four have similar catalytic efficiencies for β-lactam hydrolysis (kcat/KM only varies up to twofold across all six MBLs). However, their catalytic efficiencies for the promiscuous PMH activity varies by ~20 fold.

We used each of these sequences as a starting point for directed evolution experiments, in which we aimed to maximise the PMH activity of the enzymes.

We transformed randomly mutagenized gene pools into E. coli, and used purifying selection to enrich for only functional variants, by plating the libraries onto agar plates containing a low ampicillin concentration. Per round, we inoculated a total of 396 variant colonies individually into 96-well plates containing liquid media. These were regrown, lysed and screened for PMH activity. We isolated and sequenced the most improved variant(s) and used them as templates for the next round of evolution.

Within the first two rounds of evolution, we noticed that the orthologs that shared higher similarity showed similar improvements in fitness, regardless of their fitness starting point (compare the slopes of EBL1 with NDM1, and VIM2 with VIM7, in the figure below). Thus, we proceeded with directed evolution only for representative orthologs, i.e. VIM2 and NDM1.

We also noticed that fitness seemed to be plateauing by round 7-8. Hence, purifying selection was replaced by a pre-screening for variants with increased PMH fitness in rounds 9-10 (see schematic above). No variant with increased PMH fitness was isolated, confirming that a fitness plateau had, indeed, been reached.

[Directed evolution schematic, and a plot of the fitness change per round - side by side, perhaps?]

It is important to note that ‘PMH fitness’ is defined as the level of PMH activity in E. coli cell lysate. As a result, it is a function of both catalytic activity and soluble expression levels in the cell. For example, fitness differences between NDM1 and VIM2 wild-type are due to kinetics, not solubility. By contrast, EBL1 and VIM2 wild-type have similar catalytic efficiencies, but their PMH fitness differ by 35-fold due to large differences in protein expression (Put in Figure 1A and Figure 1—figure supplement 1C here).

Genetically different variants took independent evolutionary trajectories

While both NDM1 and VIM2 generally improved in PMH fitness, their evolutionary outcomes were substantially different. Initially, NDM1-WT was ~4-fold less fit than VIM2-WT. However, by the end of the experimental evolution (Round 10), their order had reversed, with NDM1 having a PMH fitness ~28-fold higher than VIM2.

By the end of the experiment, NDM1's PMH activity had increased by a factor of around 3600, while VIM2's had only increased by a factor of ~35.

Although the two WT enzymes had almost identical physicochemical properties (protein solubility, stability and structure), they clearly had substantially different potentials to evolve PMH activity. This prompts one to ask what kinds of mutations and structural changes occurred in these two variants, in each round of evolution. This is summarized in the figure below.

It is immediately apparent that unique mutations arose in each variant. Only two mutations occurred at the same position, and these were mutated to different amino acids. The distribution of mutations is also different. The mutations acquired in NDM1 are scattered relatively evenly around the active site. On the contrary, those in VIM2, 6/15 mutations occurred within or near loop 3.

This suggests that the genotype at the starting point affects the evolutionary potential of a cryptic phenotype. We can now ask what happens if mutations are introduced into WT versions directly. Also, are mutations acquired by NDM1 deleterious if acquired by VIM2? These address if evolution is constrained by starting point, and if so, how?

Genotypic starting point limits accessibility of adaptive mutations

The best way to test whether or not the starting point matters is to perform experimental evolution with multiple replicates and see if evolution is repeatable. This was not feasible with our experimental design. Therefore, we used alternative methods to address this question.

The first method we employed was to replay R1. We generated and screened three additional mutagenized libraries from each wild-type enzyme. To our surprise, we isolated mutations at the same position for both variants. This strongly suggested that each starting genotype benefits only from a subset of mutations.

We could also reintroduce the mutations that get fixed in each round of evolution directly into their wild-type counterparts, and ask whether the order in which mutations are acquired matter. If yes, this would further support that the starting point matters in the process of evolution. This effect is called epistatic constraint.

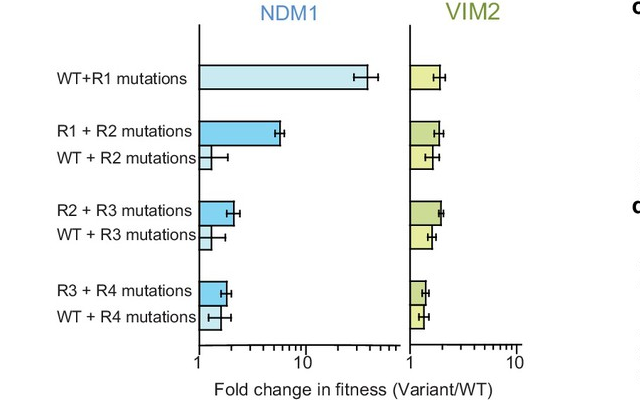

We found that introducing R1 mutations alone into wild-type NDM1 improved its fitness ~40-fold. Doing the same with R2 mutations alone barely had an effect. Introducing R2 mutations in the background of the R1 mutation further improved NDM1-R1’s fitness. This means that for NDM1, the starting point is really important in determining the improvement in fitness. This effect is called epistatic constraint.

For VIM2, though, it seems that the order of acquiring mutations does not matter. Adding R1 mutations alone, or both R1 and R2 mutations, led to a similar improvement in fitness.

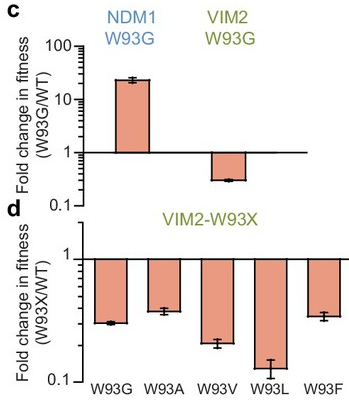

The R1 mutation that had the strongest fitness effect on NDM1 was W93G (see Fig 2B). To ask why different mutations came up in R1 of evolution with NDM1 and VIM2, we reintroduced the W93G mutation into both NDM1-WT and VIM2-WT and measured the improvement in fitness.

As expected, NDM1’s fitness improved. Interestingly, VIM2’s fitness decreased. This means that the W93G mutation is deleterious in the VIM2 background. In fact, replacing W93 with any residue reduced VIM2’s fitness. Hence, even though VIM2 and NDM1 are similar in their physicochemical properties, the same mutation has a polar opposite effect on them.

It might seem obvious that a mutation beneficial to one variant is detrimental to another. But this is exactly the point of cryptic genetic variation: highly similar variants can show dramatically different responses to evolution, which is constrained by their starting point.

An interesting aspect to note is that when faced with an environmental change, the enzyme not only evolves to become better at the non-native function, it can often be constrained to by its native activity. Going back to our charcoal-lactose example, if introducing charcoal does not negate the need to metabolize lactose, mutations in the enzyme that improve charcoal metabolization without affecting lactose activity are beneficial over ones that do. Conversely, if charcoal metabolization interacts negatively with lactose and lactose is not necessary for survival, then mutants that improve charcoal activity while reducing lactose activity are beneficial over ones that don’t. To look at this, we measured at the PMH and beta-lactamase activity of our mutants.T It is also important to note that the same mutation can have differential effects on native and non-native activity. For example, tThe W93G mutation in NDM1 not only improves PMH activity nearly 100-fold, but also increases beta-lactamase activity only 2-3-fold. [Supplementary 2A] In comparison, the same mutation in VIM7 has polar opposite effects on the two activities, improving PMH, but decreasing beta-lactamase activity.These confounding effects on native and non-native functions may confer distinct fitness advantages dependent on how precise nature of the enviromental change.

Fitness is a combination of expression level and catalytic activity.

The conventional idea is that the more stable or the more soluble a protein, or the greater its functional expression, the more evolvable it is. These properties are thought to help stabilize deleterious mutations and allow for more adaptive mutations to accumulate. However, NDM1 and VIM7 have very similar properties and expression [see Fig ____], but take completely different evolutionary trajectories.

How can one explain this result at the molecular level? To do so, we measured a range of molecular properties over the rounds of evolution - catalytic efficiency, soluble expression, melting temperature, and oligomeric assembly.

Let’s start off with NDM1. In R1, its catalytic efficiency increased ~300-fold, but its solubility decreased from 43% to 25%. Thus, its fitness increased only by ~20-fold. The decrease in solubility from R1 never quite recovered. Catalytic efficiency continued to increase, however, which is reflected in the fitness increase of NDM1.

Looking at the same figure above, one can see that VIM2 evolved via a completely different molecular pathway - over evolution, its catalytic activity only showed a modest improvement, but its solubility increased. It is also interesting to note that VIM2 evolved to exist in an equilibrium between its monomer and dimer forms. This matters even more because the catalytic efficiency of the dimer is lower than that of the monomer.

In sum, our results suggest that two distinct molecular mechanisms underlie the observed differences in evolutionary trajectories. NDM1 evolved largely by improving catalytic efficiency at the cost of solubility, while VIM2 evolved largely by improving stability and solubility.

Discussion

The diverse functions of proteins that exist in life today demonstrate that amino acid sequences are able to evolve to perform novel functions, and researchers have been able to see examples of such adaptation in real time. This suggests that biological molecules have a remarkable degree of evolvability. These successful examples of adaptation, however, may also obscure a wealth of cases where proteins have failed to adapt or were limited in their ability to evolve a new function.

The evolutionary potential of a given protein sequence would be useful to predict, especially for synthetic biologists who would like to design novel proteins with optimal activity. Would it be possible to look at a group of protein sequences and their physicochemical properties and predict which among these would evolve to have an optimum function?

Our results have shown that not all enzymes (even highly similar ones) evolve to their fitness maximum. This can be explained by the idea of cryptic genetic variation. []

For example, certain variants could have ‘pre-adapted’ alternate properties. This seems to be the case for metallo-beta-lactamases (MBLs), which have an alternative activity - phosphonate monoester hydrolase (PMH). Closely related MBLs have large differences in their PMH activity, and minor differences in their beta-lactamase activity. This suggests that it is very unlikely that the PMH activity was ever selected for. Thus, PMH activity seems to be a truly ‘promiscuous’ function.

Most protein designers try to evolve a variant that already has reasonably high activity of interest. Evolution should improve the activity of interest. One would imagine, then, that if we started off with the MBL variant with the highest PMH activity, and take it through multiple rounds of evolution, it would be more active than any other “weaker” starting point, right? Not quite.

Our evolution experiments with MBLs have shown that the starting activity does not necessarily predict the final outcome. The variant with the lower initial PMH activity – NDM1 – improved far more dramatically than its close cousin – VIM2. So much so that by the end of 10 rounds of directed evolution, NDM1’s PMH activity was ___-fold higher than VIM2’s.

Thus, our results emphasize that it is very difficult to predict the evolutionary outcomes from a given starting point, partly because there are hidden effects of genetic variation that can have significant consequences to the evolutionary trajectory of a protein.

So, getting back to our initial question – would it be possible to predict which variant to start off evolution with? Not yet, at least. But it would be possible to predict evolution if one had a deep understanding of the molecular mechanisms at play.

Contributions

Some text describing who did what.